Shrayan Sen

On the morning of 23rd September, Kolkata woke up to a city under water. Neighbourhoods across the metropolis were submerged, arterial roads were impassable, and by evening, the toll of rain-related deaths had risen. For many residents, the nightlong downpour felt like a cloudburst had struck the city. The comparison may be loose, but the intensity was undeniable: nearly 300 mm of rainfall within a span of just eight hours.

The natural question follows—why was such an extraordinary event not predicted? After all, weather forecasts had warned of heavy rain over south Bengal. Yet, the sheer scale and intensity of the downpour took citizens, administrators, and even seasoned weather-watchers by surprise.

The Forecast vs. The Deluge

In the days before the event, meteorological models clearly indicated a strong low-pressure system over the Bay of Bengal, drawing vast quantities of moisture inland. The meteorologists- even the Indian Meteorogical Department had issued warnings of “heavy to very heavy rainfall” in districts of Gangetic West Bengal, including Kolkata.

Technically, the forecast was not wrong. Heavy rain did occur, and Kolkata was within the zone of warning. What science cannot yet do is to narrow down such forecasts to the precision of time and place. It cannot declare that “between 10 pm and 6 am, central Kolkata will receive over 300 mm of rainfall.”

The Meteorological Mechanism

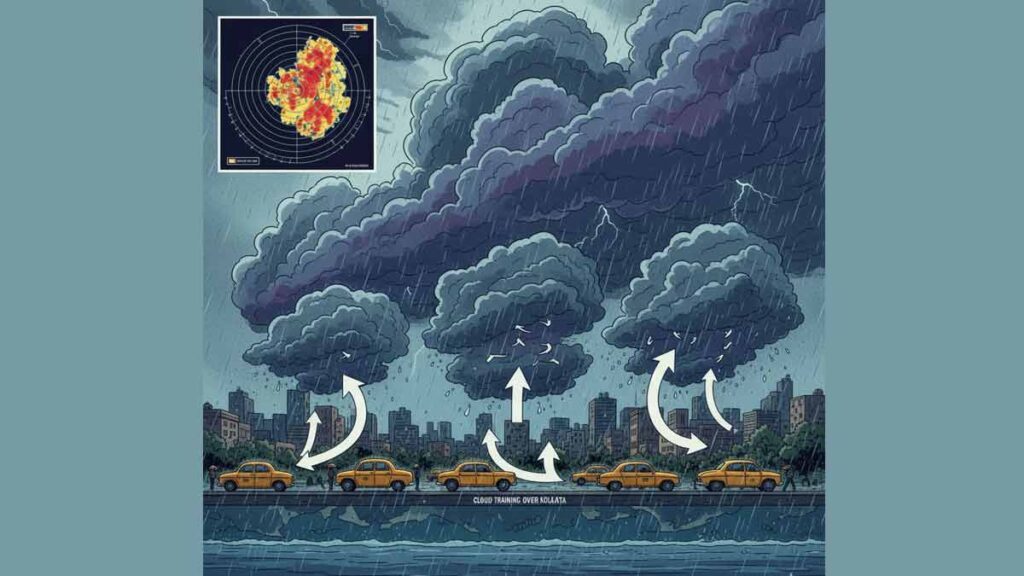

What unfolded that night was the result of successive cumulonimbus cloud formations over the city. These towering thunderclouds are known for their capacity to unleash intense rainfall. In most cases, they form, release a burst of rain, and then move away.

But on 22–23 September, Kolkata experienced what meteorologists call cloud training—a phenomenon in which multiple thunderstorm cells develop and pass repeatedly over the same geographical location. Instead of dispersing, one system was followed by another, and then another, dumping colossal volumes of water over a confined area.

Had the same systems drifted slightly westward, Howrah could have borne the brunt. If they had moved south, South 24 Parganas would have been inundated instead. That uncertainty explains why exact city-specific predictions remain beyond reach.

Why Cloudburst-Like Events Defy Prediction

Weather experts consistently underline that predicting a cloudburst—or an urban deluge akin to one—is nearly impossible. The reasons are structural:

1. Scale of Impact: Cloudburst-type events affect areas as small as 20–30 square kilometres. Most forecasting models work at grid scales much larger than this.

2. Suddenness: Cumulonimbus clouds can evolve within 30–60 minutes. Their explosive growth gives little lead time for forecasts.

3. Topographical Complexity: Even in plains like Kolkata, tiny shifts in wind or humidity determine whether a system stalls over one neighbourhood or moves on.

4. Technological Limits: Doppler weather radars and satellites can only detect severe rainfall once it begins; they cannot project six hours in advance with precision.

5. Chaotic Microphysics: The behaviour of water droplets, ice particles, and supercooled liquid in a storm cloud is inherently chaotic and resists exact modelling.

This is why forecasters avoid using the word cloudburst in city contexts. Instead, they issue broader alerts such as “extremely heavy rainfall likely over south Bengal.”

What Can Be Done

Given these limitations, meteorologists rely on nowcasting—short-term radar-based forecasts that can provide one to three hours of warning once storm systems begin to form. On the night of 22 September, radar reflectivity did indicate the build-up of intense convection over Kolkata, but by then the downpour had already begun.

For city authorities, this reality holds a hard lesson. Science may not be able to prevent, or even precisely predict, the next deluge. What can be improved is urban resilience—better drainage systems, stronger pumping capacity, and preparedness protocols for emergencies.

A Broader Perspective

The September 23 event is a reminder that urban India is increasingly vulnerable to extreme weather. Climate change is intensifying rainfall patterns, increasing the likelihood of such concentrated downpours in cities that are ill-equipped to handle them. Just as towns in the Himalayas cannot be given pinpoint cloudburst forecasts, Kolkata too must learn to interpret forecasts as probabilities rather than certainties.

Ultimately, meteorology is not a promise of exactness but a science of likelihoods. The skies over Kolkata proved that night that nature can still defy the sharpest of forecasts.

Very well explained. Thank you so much.